Photo: Marko Grubišić’s personal archive. A group of students that included Marko Grubišić and Milan Sušac.

Zagreb

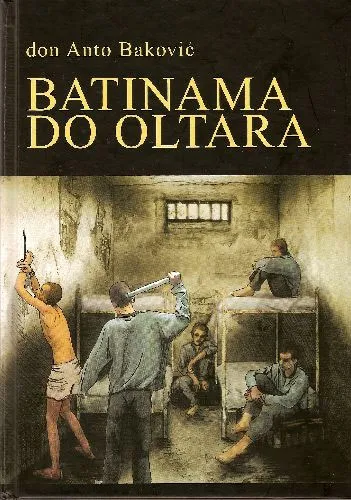

On 11 April 1983, the Council of the Zagreb District Court sentenced students Marko Grubišić to four years in prison and Milan Sušac to two and a half years in prison. They were found guilty because they sang the song “Marjane, Marjane” in the student dormitory of Lašćina, inserting in it, for Tito’s communist regime, “inappropriate” words “crven-bijeli-plavi, pod kojim su pali Zrinski-Frankopani” (“red-white-blue, under which the Zrinski-Frankopani fell”), and “još jedno slovo, ime Isusovo” (“and another word, the name of Jesus”).

Many of our cities have their own anthems. One of them is Split. The anthem of Split is a legendary song (some think it would be better to call it a canticle) “Marjane, Marjane”. The version chosen by city authorities reads in its entirety:

Merjane, Merjane/ Merjane, Merjane/ Merjane, Merjane/ Merjane, Merjane, ča berjak ne viješ?/ Ča berjak ne viješ, ča berjak ne viješ/ ča berjak ne viješ, milu trobojnicu?/ Milu trobojnicu, milu trobojnicu/ milu trobojnicu, naš berjak ervaski! Sa kojin se diči, sa kojin se diči/ sa kojin se diči, čila Dalmacija/ Čila Dalmacija, čila Dalmacija/ čila Dalmacija i mater Ervaska!’.

Translation:

Marjan, Marjan, Marjan, Marjan

Marjan, Marjan, why don’t you fly the flag,

Why don’t you fly the flag, why don’t you fly the flag

Why don’t you fly the flag, the dear tricolour?

The dear tricolour, the dear tricolour

The dear tricolour, our Croatian flag?

Of it is proud, of it is proud

Of it is proud all Dalmatia.

All Dalmatia, all Dalmatia,

All Dalmatia and mother Croatia!

It is an old and clearly popular folk song, but it is not known when and in what context it was composed. There are opinions that its beginnings should be sought in the 19th century, and some associate it with the beginnings of afforestation in the Marjan area. It may have come to life among the workers and peasants who worked on the afforestation, and it is possible that this happened because the reflections of the naval battle of Vis in 1866, when the song was allegedly first uttered or written, were still alive among the people.

It also seems that the spontaneous change of some of its parts started simultaneously with its singing. According to probably the oldest recorded variant, which was recited to the composer Antun Dobronić by Roko Britivić, a peasant from Kaštela, the whole song read:

Marjane, Marjane/ što barjak ne viješ, milu trobojnicu, naš barjak hrvatski!/ S kojim se diči cijela Dalmacija, cijela Dalmacija i mili otoci/ Koji “Re d’Italiu” u more utopi.

Marjan, Marjan/ why don’t you fly the flag, the dear tricolour, our Croatian flag!/ All Dalmatia is proud of it, all Dalmatia and dear islands/ which sank “Re d’Italia” in the sea.

The mention of an Italian armored vehicle sunk near Vis suggests the memory of the naval battle. However, at the beginning of the 20th century the song was recorded in the book by Dujam Srećko Karaman, and the (first) part, interesting to us, reads:

“Marjane, Marjane/ Što barjak ne viješ?/ Što si prizlovoljan/ Al te voja nije/ Marjane, Marjane/ Moj debeli lade/ U tebi se goju/ Sve divojke mlade!”

“Marjane, Marjane / Why don’t you fly the flag? / Why are you sullen/ And why do you bear ill will?/ Marjan, Marjan/ My dense shade/ In you grow/ All young girls!”

Karaman’s version suggests that at the time of the record, Marjan was a promenade in Split, known for its dense and soothing shade. At the same time, the song entered political life. When the People’s Party defeated the Autonomist Party in the municipal elections in Split in 1882, a song with the following text was allegedly shouted in the city:

“Marjane, Marjane, ča barjak ne viješ/ milu trobojnicu, naš barjak narodni/ Crven, bili, plavi – to je barjak pravi/ ko se pod njim vije, kukavica nije!”

“Marjan, Marjan, why don’t you fly the flag/ dear tricolour, our national flag/ Red, white, blue – that’s the true flag/ those who fight beneath it, are not cowards!”

The political use of the song will prevail in the coming decades. Let the reader not resent the citation of all these variants, but it is necessary for a better understanding of this story. In the interwar period, the text of the poem was set to music on several occasions, and Ivo Tijardović also did it. His version is today mostly accepted as the anthem of the city of Split, with one big difference, however: in his variant, the verse “our Croatian flag” is omitted. Tijardović’s reasons probably lie in the opinion that this verse would be unacceptable to the Serbian royal regime of Karađorđević. In the meantime (1920s and 1930s), Serbian imperialism in the cloak of Yugoslavia became the main enemy of Croatian national interests, which again (apparently) conditioned a new change in the song. According to some data, the song was popular in the ranks of the Party of Rights youth in the following form:

“Marjane, Marjane/ ča barjak ne viješ/milu trobojnicu, naš barjak hrvatski/ Crven, bijeli, plavi to je barjak pravi/ tko se pod njim vije, kukavica nije/ a tko se ne vije, bolje da ga nije!”

“Marjan, Marjan, why don’t you fly the flag/ dear tricolour, our national flag/ Red, white, blue, that’s the true flag/ those who fight beneath it, are not cowards/ And they who don’t, better they not be!”

Another step in changing the song was taken by the Partisan Silvio Bombardelli. His version reads:

“Marjane, Marjane, ča barjak ne viješ/ milu trobojnicu, naš barjak slobode/ Crven, bijeli, plavi, to je barjak pravi/ na njemu se čita ime druga Tita, a na drugoj strani – naprijed, partizani!/ I na vrh barjaka – zvijezda petokraka.”

“Marjan, Marjan, why don’t you fly the flag/ the dear tricolour, our flag of freedom/ Red, white, blue, that’s the true flag/ on which is read, the name of Comrade Tito, and on the other side – forward, Partisans!/ And on top of the flag – a five-pointed star!”

The new Communist regime completely adopted Bombardelli’s version. It has become one of its untouchable symbols. For the first time in its history, a change of a verse or a word could lead the author to long prison terms. This is exactly what happened on 11 April 1983, when the Council of the District Court in Zagreb sentenced Marko Grubišić to four years in prison and Milan Sušac to two and a half years in prison. According to the verdict, the accused were found guilty because on the night of 24 October 1982, at the student dormitory Lašćina, at the celebration of a student’s birthday, they allegedly sang “on several occasions and out loud” the song “Marjane, Marjane”, and in such way that they inserted the words “red-white-blue, under which Zrinski-Frankopani fell”, and “another word, the name of Jesus”. These verses, undoubtedly provocative for the judicial council, provoked “anxiety, revolt and reaction” of a certain Serbian student.

Denounced by another student

It should be noted that he himself did not hear Grubišić and Sušac sing the incriminated verses, but was allegedly informed about it by a student in whose room the birthday party was held. In any case, around 3 a.m. the upset and revolted student decided to react, so he informed the secretary of the League of Communists in the Lašćina dormitory. The next day, on 25 October 1982, late in the evening at around 11 p.m., Grubišić and Sušac allegedly physically abused the informant. The rest of the series of events is simple: police investigation, indictment, trial, conviction and imprisonment.

We will not pay special attention here to phenomena that strongly point in the direction of a rigged trial. Notable, there are striking inconsistencies in the statements of key prosecution witnesses – one said he was sure that one group sang “red, white, blue, that’s the true flag, under which Zrinski-Frankopani fell”, the other group “forward, Partisans”, while not hearing that anyone mentioned “the name or heart of Jesus”; the second witness stated that one group sang “forward, Partisans”; another group “the name of Jesus”, and he did not hear the mention of “Zrinski and Frankopani”; the third witness stated in the investigation that he only heard the mention of “the heart of Jesus and Zrinski and Frankopani”, while at the trial he stated that he heard only the singing of the song in the “original form by which he means the version mentioning the name of ‘Comrade Tito’ and ‘forward Partisans’”. These inconsistencies do not allow the exact form of the song used to be determined. Other facts pointing to a rigged trial include rejecting the testimony of numerous other witnesses (at least three consistently testified that they had never heard anyone sing the song in any of its form), as well as the controversial information that the only witness of the attack is also the (alleged) victim of the attack. Grubišić and Sušac were convicted of a form of verbal delict or verbal political delinquency which was substantially less analyzed in our country. This was a notorious article 134 (paragraphs 1 and 3) of the Criminal Code of Yugoslavia, i.e. the criminal offense of inciting and provoking national, racial or religious hatred, discord or intolerance among the peoples and nationalities of Yugoslavia living in the SFRY, which then caused riots and violence. As this offense was found in chapter XIV of the Federal Criminal Code (criminal offenses against the foundations of the socialist, self-governing social order and security of the SFRY), the alleged singing of a few verses caused Grubišić and Sušac to gain the status of arrested, convicted and punished enemies of the state.

Compared to the much more analyzed cases of classical delict of opinion (article 133, paragraph 1), in such cases the regime did not actually have to resort too much to rigged trials. Defined by law and in full dependence on the position of the court, two phenomena were crucial, both of which fall within the framework of the phenomenon of hostile propaganda. Namely, Grubišić and Sušac knew in advance that the incriminated verses were a hostile distortion of historical truth, and with that knowledge, i.e. aware that it was an enemy act, they deliberately decided to sing them, having previously planned to hurt someone’s national feelings by pronouncing hostile words. In order to show Grubišić and Sušac’s counter-revolutionary intent or aim, the judicial council only had to declare the verses a hostile historical falsification, the pronunciation of which allegedly undoubtedly violates the national feelings of the Serbs.

Let us look at how the judicial council committed this dishonorable act. At the beginning, it was ruled that Grubišić and Sušac changed the authentic text of the revolutionary song “Marjane, Marjane”. This, of course, was an obvious lie as one of their lawyers showed in detail. It is clear from the above that there numerous and different versions of the song existed, and that the Partisans themselves used several versions. In other words, it was not at all possible to establish a change in the genuine version of the song because there was no genuine version of the song, even in the Partisan period! The Supreme Court predictably rejected the defense’s argument, adding in the second instance verdict that their alleged hostile intent was evident in the fact that they “glorified persons from Croatian history” (Zrinskis and Frankopans). Thus, it was further stated, “they were aware that by such a way of singing (i.e. by allegedly changing the authentic text and mentioning the Zrinskis and the Frankopans) they could provoke and incite hatred and discord towards a group of persons of another nationality.” It is worth pausing here because both courts have declared that the mention of the names of two noble families from the 17th century is also conducive to provoking national intolerance, hatred and discord. More precisely, the mention of the Zrinskis and the Frankopans hurt the national feelings of the Serb students.

Let us look at the arguments of the defense. At the time of sentence pronouncement, Zrinski and Frankopans had been dead for about three centuries. In Zagreb, there were Nikola Šubić Zrinski Square, Katarina Zrinski Square, Petar Zrinski Street and Frankopanska Street, and they were mentioned in every history textbook.

Prominent family members subsequently perished in battle with the Austrians, having previously clashed with the Ottomans. The Serbs themselves, whom they sometimes allowed to settle on their estates, thus rescuing them from violent Turks, were grateful to them, which they often later mentioned in newspapers and publications. Finally, Zrinskis and Frankopans became an integral symbolic value of Croatian national identity, which even the regime itself did not deny. How, then, could the mention of Zrinskis and Frankopans offend any Serb? The federal court reduced Grubišić’s sentence to two and a half, and Sušac’s to a year and a half in prison, mainly for the view that the (alleged) attack on one man was not the same as causing mass riots. The interpolation of Zrinskis and Frankopans in the song “Marjane, Marjane” still remained part of a broader hostile plan to provoke national intolerance, hatred and discord.

Regardless of the unfortunate fate of Grubišić and Sušac (and probably precisely because of such verdicts), the number of singers of the song “Marjane, Marjane” grew relentlessly in the following years, neither, of course, in the “authentic revolutionary variant”, nor – and this was even more devastating for the regime – in the version that was allegedly sung on the night of April in a student dormitory in Zagreb. In the second half of the 1980s, the most widespread version of the song read: “Marjane, Marjane, why don’t fly the flag/ the dear tricolour, our Croatian flag/ Red, white, blue is the true flag, those who fight beneath it, are not cowards! And those who don’t, better they not be. And another word – the name of Jesus”. This variant was especially widespread in Dalmatia, and caused quite a public scandal in April 1989, when it was sung at a basketball match between Jugoplastika and Belgrade’s Partizan. All of it also attracted the attention of foreign journalists who began to ask embarrassing questions to the regime’s party leaders. “What harm is it if someone sings?”, a journalist from Germany asked the Split leaders, “and in that context, is ‘Marjane, Marjane’ an old Croatian song?” Again, the regime did not learn anything: new trials were held (although for political misdemeanors), and the media called the singers of this song nationalists and fascists. A year after the aforementioned match, the song remained, and Tito’s communist regime disappeared from the historical scene.

Source: Večernji list, 21 March 2021

Editorial/komunistickizlocini.net