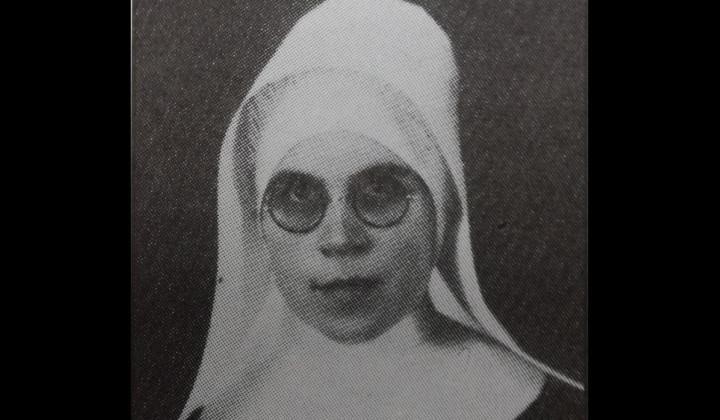

Sister Alojzija (Štefica) Caratan, Sister Ljiljana (Katica) Abianac, Sister Maristela (Marica) Dolenec,

Daughters of Divine Charity

We bring you a brief account of the prison days of six martyrs, nuns of the Congregation of Daughters of Divine Charity, in post-war communist prisons, who were convicted although innocent, and whose indictments were never found.

The Congregation of the Daughters of Divine Charity, dedicated to education of female youth, was founded in Vienna in 1868 by teacher Franziska Lechner. After the re-establishment of the church hierarchy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Archbishop of Sarajevo, Dr. Josip Stadler, invited the sisters to Bosnia in 1882. The founder immediately responded to the invitation and, together with the Austrian and Slovak sisters, founded two schools and the Institute of St. Joseph in Sarajevo in 1882, and the Institute of the Queen of the Holy Rosary in Tuzla in 1883. In addition to the institutes, farms were set up to feed the sisters, girls and poor children: “Betanija” near Sarajevo and “Josipovac” near Tuzla. At the invitation of the Franciscan Father Franjo Franjković, they also opened a primary school in Breške not far from Tuzla. In 1893, the congregation also built the Sarajevo Institute of St. Augustine, where a German language school was housed.

A gift of enlightment to Bosnia and Herzegovina

Girls from all over came to the Sarajevo Institute, not only from Bosnia and Herzegovina but also from Croatia. An important historical fact is that the far-sighted founder, sister Franziska Lechner, founded the first Women’s Teachers’ School in Sarajevo, which educated many teachers, which was a great gift to Bosnia and Herzegovina in the form of enlightenment and education of female children. From the very beginning, new school buildings were built and expanded because it was always crowded due to the growing number of students, until the institute gained its final appearance with the church of the Queen of the Holy Rosary – the sacral beauty of Sarajevo. The school was attended by children of all nationalities. In addition to the teachers’ school, the institute also had a primary school and various vocational schools.

The Institute of St. Joseph in Sarajevo flourished between 1900 and 1918, when Croatian girls from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia started to enroll in the convent and gradually replace foreign sisters who were dying, or had to return to their homeland after World War I. With the disintegration of Austria-Hungary in 1919, the Province of God’s Providence became independent, with the seat of the provincial administration in Sarajevo. However, during later history, there were difficulties and trials, especially during the Kingdom of SHS and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, as shown by the monastery chronicles.

During World War II, despite enormous difficulties, especially with regard to nutrition, nursing schools did not cease to operate. The diligent sisters, whose 83 graves are strewn across “Betanija” managed to feed everyone; they worked, all the time in fear for their life. During the war, the sisters suffered a severe blow in the massacre of the Drina martyrs in Goražde and Romanija, and the burning of Mary’s home in Pale by the Chetniks on December 15th, 1941. It is well worth remembering these martyrs, servants of God: sister Jula Ivanišević, sister Berchmana Leidenix , sister Krizina Bojanc, sister Antonija Fabjan and sister Bernadete Banja.

Cake and seven roses on a tray

The Congregation of Daughters of Divine Charity, as well as other congregations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, suffered a terrible blow in in 1945, when communist Yugoslavia confiscated all their schools and monastic buildings, and forbade them from wearing religious robes. Within 24 hours, the sisters had to leave all the institutes, farms and the resort of St. Anthony in Ilidža. Some sisters found accommodation in the Franciscan monastery in Fojnica, some went to relatives, others tried to take refuge in Croatia. However, new post-war persecutions ensued: summoning teacher sisters and principals to court, interrogation, arrests and imprisonment. Many of the sisters were interrogated and paraded into the courtroom and interrogation room, as if they were criminals, under armed escort. They were interrogated day and night. On occasion, as many as six armed partisan officers were present during interrogation.

Some of them became prisoners sentenced to severe imprisonment overnight: S. M. Maristela (Marica) Dolenec was born on February 27th 1907 in Koprivnički Ivanec to father Stjepan and mother Dora, née Sipuš, and she became a nun on August 6th 1927. She taught as a teacher at the Institute of St. Joseph in Sarajevo. After the war, the heads moved her to Koprivnica, but one day OZNA came to pick her up and an armed soldier escorted her by train to a prison in Sarajevo. According to a later story, during the trip she gave him pears she took with her. She spent 5 years in prison, mostly in Zenica, of which seven months in solitary confinement. Her indictment simply disappeared and was never found. She prayed that God would give her a sign that her imprisonment was His will.

One day a guard brought her a tray of cake with seven roses on it. Sister Maristela was surprised, because no parcels usually reached her. She gave the cakes to the guard and kept the roses for herself, remembering it was the day of the feast of the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary. She took this as Our Lady’s sign and message that it was better that she was in prison, rather than her students. She never found out who sent her roses and cakes, but since then she found it easier to endure prison hardships and loneliness. After prison, she was head nurse at a retirement home in Travnik. She worked conscientiously and responsibly for over 20 years. At the same time, she was the head of the monastery in Travnik and later in Granešina near Zagreb, and for several years a provincial economist. She died in Zagreb on October 17th, 1994. She was buried at Mirogoj cemetery in Zagreb.

An unsuccessful plea to the commissar

Sister Filomena (Marija) Zavodnik was born on October 4th, 1900 in the Slovenian town of Sveti Martin Štaj to mother Marija Zavodnik, while her father’s name is unknown. She finished elementary school and became a nun on August 6th, 1927. She was imprisoned in Zenica after being accused of “being in cahoots” with the Germans. Her indictment has not been preserved either. She could not do anything in prison because she was helpless and she later went to Austria. She died in Breitenfurt on May 31st 1977, where she was buried.

Sister Alojzija (Štefica) Caratan was born on February 8th, 1905 in Višegrad, Bosnia, to father Jure and mother Antonija, née Crnić. Her father was a lawyer and a very wealthy man. Štefica became a nun on March 20th, 1929; she studied at the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb and spoke German. As early as 1935, the headmistress appointed her director of the Institute of St. Joseph in Sarajevo. She was in solitary confinement for a year in the attic of a prison in Albaharijeva Street, even during a severe winter. Her father tried to bail her out though a political commissar, but without success. She was in prison in Sarajevo and Zenica for a total of 14 months. After prison, she came to Zagreb and got a job at the Old Church Slavonic Institute. She never wanted to talk about her prison days, and she passed away in Zagreb on July 4th, 1995. She was buried in Granešina near Zagreb.

Sister Paulina (Slavka) Jergović was born on April 26th 1909 in Sarajevo to father Marko and mother Sofija, née Paškvan. She became a nun on August 15th, 1933, and as a teacher she also taught at the Institute of St. Joseph in Sarajevo. She was a great mathematician. She spent five years in prison in Zenica. No one had ever seen the indictment, and she kept forever silent about her prison days. She died on July 25th, 1990 in Granešina near Zagreb, where she was buried.

Sister Huberta (Brigita) Ciglar was born on January 6th, 1912 in Lukavac near Tuzla to father Josip and mother Berta, née Sudikatus. She became a nun on August 15th, 1933, and by profession she was a teacher and organist, so she taught at the Institute of St. Joseph in Sarajevo. After the war, she was transferred to Supetar on the island of Brač, where she was arrested by the OZNA and taken to Split, and from to the Sarajevo prison. She spent three years in Zenica prison on charges of giving iodine and bandages to an Ustasha. There is no indictment for her either. She died on August 15th, 1998 in Split, where she was buried.

Sister Ljiljana (Katica) Abianac was born on December 15th, 1919 in Bodovaljci near Nova Gradiška to father Ivan and mother Terezija, née Ivanišević. She became a nun on February 2nd, 1940. She was a teacher and organist by profession. She spent two months in prison in Sarajevo, and no one could get an indictment against her. She later worked as a catechist and educator for girls. She died on October 19th ,2005 in Granešina, where she was buried.

Cross and rosaries made from bread

The sisters were usually deprived of everything; some were allowed to keep a breviary. The rosaries and the cross on the wall were made from bread. The hardest was solitary confinement, full of rats. Quite exceptionally, sister Huberta Ciglar was allowed to keep a suitcase, which she used as a pillow for five months. The guards would often bring the soup to the door, and then spill it. They would open the packages and sprinkle the food in them with tobacco to make it inedible. Sister Huberta was threatened by a guard, who said he would slaughter her like an animal if only he was in charge for five minutes. It was his duty to light the fire from the outside but he deliberately kept her stove cold.

Huberta wrote, however: “We wanted to confess and receive communion, but how? The priests occasionally gave us absolution from the other side of the terrace because there was no other way. In addition to our sisters, there were also sisters of the Blood of Christ, two sisters of St. Cross, one Franciscan, and Sisters of Mercy. There were about 20 nuns and 25 ladies and girls in one big room.

Maristela worked in the sewing room, sister Paulina and I knitted, and sister Filomena was old and could do nothing. We had a norm, and I was lagging behind, so the guard yelled at me. One forester secretly brought us consecrated hosts sent by a priest. We received communion in secret. We cried with joy. We celebrated Christmas in secret. Once we even dared to bring in a Christmas tree. I put baby Jesus under the tree. A guard came and told me to remove that “baby” before the warden saw it.

There was hard labor. We walked for seven kilometers. The riverbed needed to be diverted, so we dug a canal to do so. We had different sized boots on our feet. One foot size 45 and the other size 40. We filled the carts with that muddy earth. It was very difficult. As if they just wanted to torture us. I once said that I’d had enough of partisan songs. From then on, I had to play only those songs. Then I was thrown into solitary confinement. I was taken out of solitary confinement when a woman hanged herself in solitary confinement. I was taken back to the sisters. In Zenica, they took our frocks and gave us overalls. The trouser legs were so long I had to roll them up three times. We slept on the floor. We lay like sardines next to each other. It was hard to the point of being unbearable. My feet were very swollen from the heavy boots.”

Source:

Glas Koncila, no. 19, May 10th , 2009

Editorial board/crimesofcommunism.net