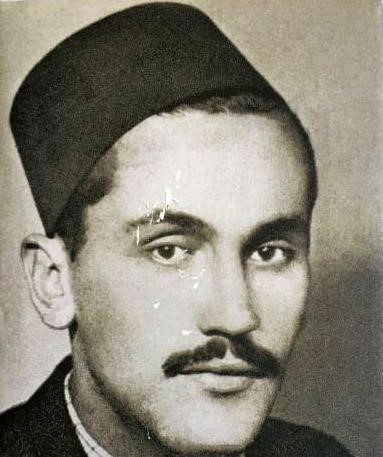

Jerko (Jerolim) Skračić, born in Murter on 13 May 1918 – killed by Tito’s Partisans in 1945 or 1947, Croatian writer and journalist.

Jerko (Jerolim) Skračić

He attended primary school in his native Murter, the Franciscan gymnasium school in Preko and the classical gymnasium school in Šibenik. In 1940, he commenced law studies in Zagreb. He was a political prisoner in Lepoglava, which he described in the book Pod drugim ključem: sjećanja na život ustaških zatočenika u Lepoglavi 1940. i 1941. god (Under Another Lock and Key: Memories of the Lives of Ustasha Detainees in Lepoglava in 1940 and 1941), which was published in 1942. After his release from prison, he spent a short time in Berlin, and during the NDH he was the director of the Radio Station in Sarajevo, then the editor of the Zagreb weekly Hrvatski krugoval. He collaborated in Hrvatska revija, Glasnik sv. Ante and other magazines. He also published a collection of novellas Osunčani otoci (The Sunny Islands) (1944) and Stihovi (Verses) (1945). With the arrival of the Partisans in Zagreb, Skračić set out on the Way of the Cross. He was presumably killed on the way to Bleiburg, however, according to some more reliable sources, he died later as a result of abuse, after he was imprisoned for two years by the Communist regime.

This article presents a collection of short stories Osunčani otoci (The Sunny Islands) by Jerko Skračić. The author first presents two short stories that preceded this collection published in 1943. Novellas “Braco” and “Kolporter” point to two dominant determinants of Skračić’s future novellas: the family as content and the dramatic structure of the content. The collection Osunčani otoci has three sections. In the first (“Sjene uspomena”, “Shadows of Memories”), J. Skračić brings up memories from his childhood in first-person singular form. In the second chapter (“Osunčani otoci”, “Sunny Islands”), in the novellas of “one day”, Skračić writes about the events and current crises of consciousness of lonely people on the Kornati islands. The third section (“Selo u brizi”, “The Worried Village”) consists of romanesque, moreover dramatic, stories from family life in a closed rural world. The novellas of these two sections are written in the third-person form. One part of J. Skračić’s short stories is structured in accordance with the main theoretical postulates of this type of prose. A number of stories, however, are composed on a romanesque, longer period, matrix. The reason for this is the dramatic psychological situation of individual characters, especially emphasized by family relationships and the family’s attitude towards the rural environment. J. Skračić as a writer, following the example of great French and Russian novelists, remains an impartial witness to the events. But one cannot fail to notice his empathy with the consciousness of the characters in crisis, but also the “sad and ironic” view of the world in which they live.

His known works:

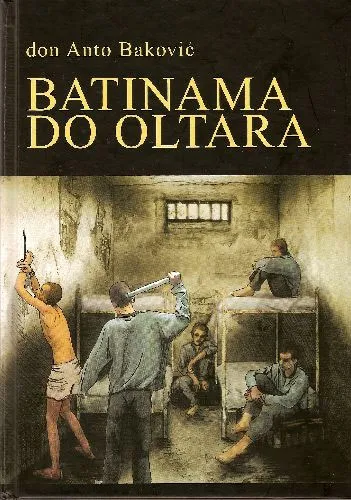

Pod drugim ključem: sjećanja na život ustaških zatočenika u Lepoglavi 1940. i 1941. god (1942) (Under Another Lock and Key: Memories of the Lives of Ustasha Detainees in Lepoglava in 1940 and 1941)

Osunčani otoci (1944) (The Sunny Islands)

Stihovi (1945.) (Verses).

A special group of people became a real “concern” of Tito’s liquidators, and that is intellectuals. To get an idea of what communist hardliners think of this category of citizens, it is enough to recall what Lenin said about them. When asked by Maxim Gorky, who asked him in 1919 to be more merciful to several scientists, Vladimir Ulyanov replied sharply: “these cowardly intellectuals, the lackeys of capitalism (…) consider themselves the brains of the people,” but “in reality it is not brain, but shit.” Under such a premise, it is clear that those Croats, who have not made the right choice, can expect the worst. On 18 May 1944, the poet Vladimir Nazor announced that all those who had collaborated with the enemy and spread propaganda by word, gesture or letter, especially in art and literature, must be labeled as enemies of the people and punished by death, and in some exceptional cases by imprisonment. This statement at least has the merit of being clear. French consul in Zagreb, André Gaillard, will soon call this a state of “red terror”.

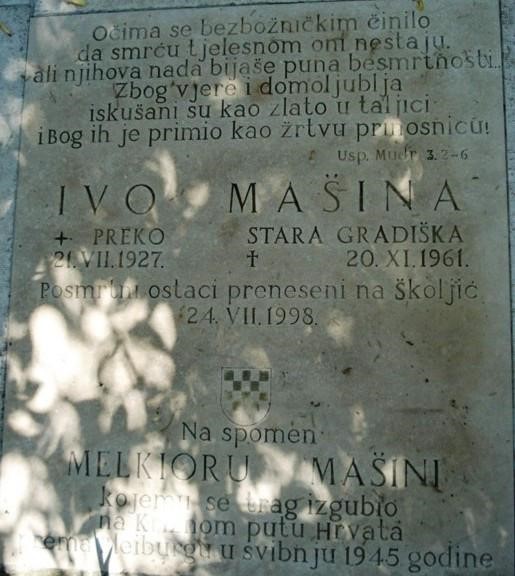

The goals of the “purges” by AVNOJ are executed swiftly and their effects are appalling. The hunt for unsuitable intellectuals is open at Bleiburg, as in all parts of Croatia. In this turmoil, writers disappear: Mile Budak, Ivan Softa, Jerko Skračić, Mustafa Busuladžić, Vladimir Jurčić, Gabrijel Cvitan, Marijan Matijašević, Albert Haller i Zdenka Smrekar, as well as poets Branko Klarić, Vinko Kos, Stanko Vitković i Ismet Žunić. Those who avoided death are sentenced to long prison sentences, such as Zvonimir Remet (life sentence), Petar Grgec (7 years), Edhem Mulabdić, Alija Nametak (15 years) or Enver Čolaković. Thanks to their relative gentleness, some have it better, like poets Tin Ujević, Abdurezak Bjelevac or historian Rudolf Horvat, who are forbidden to publish.

Journalists, on the other hand, since they are considered particularly detrimental, undergo a real massacre. The following were killed: Josip Belošević, Franjo Bubanić, Boris Berković, Josip Baljkas, Mijo Bzik, Stjepan Frauenheim, Mijo Hans, Antun Jedvaj, Vjekoslav Kirin, Milivoj Magdić, Ivan Maronić, Tias Mortigjija, Vilim Peroš, Đuro Teufel, Danijel Uvanović and Vladimir Židovec. Their colleagues, like Stanislav Polonijo, disappear in Bleiburg or are convicted. Mladen Bošnjak, Krešimir Devčić, Milivoj Kern-Mačković, Antun Šenda, Savić Marković Štedimlija, Rev. Čedomil Čekada and Theodor Uzorinac were sentenced to long prison terms.

Repression has broad consequences. The journalists and writers are far from being the only ones passing through the mill of the Polling Commission on Establishment of Crimes Based on Cultural Collaboration with the Enemy. “Great fear”, according to Bogdan Radica, “reigns in Croatia, where thousands of citizens are forced to answer to inquisitorial questionnaires (the famous Questionnaire). Artists, scientists, judges, physicians, hospital staff, members of scientific and sports institutions are all targeted, and for those who do not comply with the new rules, the punishment is immediate. Among those who are severely “punished”, let us mention architect Lovro Celio Cega, diplomat Zvonko Cihlar, banker Emil Dinter, naval engineer Đuro Stipetić (rector of the University of Zagreb) or physicians Šime Cvitanović and Ljudevit Jurak – all of whom were killed.

For musicians, punishments are lighter: the composer (a Franciscan friar) Kamilo Kob gets 6 years in prison, his colleague Zlatko Grgošević six months of forced labor, while the famous maestro Lovro von Matačić spends 10 months behind bars, and his colleague Rado degl’Ivellio is expelled from the National Theater. The painter (and priest) Marko Ćosić was sentenced to 10 years in prison, and the sculptor Rudolf Švagel-Lesica to 5 years. The painters Oto Antonini, Ljubo Babić and Rudolf Marčić are more fortunate, as they are simply forbidden to exhibit. The purge initiated by the political police is very systematic, so that various people, often with no connection to politics whatsoever, go to prison, such as singer Viki Glovacki, photographer Ljudevit Kowalsky, geographer Oto Oppitz, financier Branko Pliverić or orientalist Hazim Šabanović.

Communists burn books and clean the libraries of undesirable authors

This purge of unprecedented brutality causes deep trauma in Croatian society, all the more so because it is accompanied by a massive and permanent emigration of those who managed to slip through the net. The Communists, in order to complete the work of erasing the culture, continue at the same time to purge the libraries, either public or private, in order to eliminate all “bad” references. Thus, the works of “Ustashas” (including editions of works by Racine, Hugo or Dostoevsky, whose only “flaw” is the use of the official orthography of the NDH) as well as the “enemy books”, i.e. all those written in Italian or German language, are attacked. Texts by Nietzsche, Kant and Dante are thrown, as are translations of Aeschylus, Homer, Sophocles, Euripides, and Tacitus. The head of agitprop, Milovan Djilas (a future favorite of the Liberals from Saint-Germain, an intellectual neighborhood in Paris where leftists gather) proposes in January 1947 that Roald Amundsen’s books, as well as the works of Bernard Shaw and Gustave Flaubert, be thrown away. In any case, for those who want to self-cultivate, the works of Marx, Lenin and Dietzgen, or new chiefs of thought such as Djilas, Kardelj and “Uncle” Janko (Moša Pijade), remain.

After this short and frightening panorama, it seems possible, without exaggeration, that the Communist purges in Croatia can be called an aristocide. The cruel and insane “witch hunt” was never aimed at punishing some “fascist criminals”, but to kill the alleged hostile intelligentsia and thus deprive Croatia of its opportunities, but also to empty the house and give room for a new regime. Unfortunately, this operation fulfilled its goal perfectly, so it will take Croatia more than 25 years to build a new elite worthy of the name, and then another 20 years to finally get out of the Yugoslav communist nightmare.

Source:

from the book Hrvatska 1945.: obezglavljeni narod (Komunistički aristocid nad Hrvatima) (Croatia in 1945: a disoriented people (Communist aristocide of Croats)), Christophe Dolbeau – translated by Tomislav Sunić (from French to Croatian).

Editorial/crimesofcommunism.net